Monochrom Shadows

If you’re into classic black-and-white movies, and you want to duplicate their look with your photography, what do you do? You could shoot with film, which is the same medium that recorded those classic movies. But what if you want to shoot digital? That’s where the Leica M Monochrom camera comes in. I’ve been using it for six years. But I’m just getting to the point where I can recreate—at least partially—the shadowy, world of my favorite classic films.

What makes the Monochrom so special? There’s no Bayer filter, which most color digital cameras use to split the incoming light into three primary colors. Take away the Bayer filter, and you can’t do color. However, every pixel will receive the full amount of light without an extra layer of digital processing. As a result, the Monochrom images are a full-stop brighter. They have a wider dynamic range. And the high-ISO noise is more film-like.

That’s all good in theory, but what does it mean in practical terms? You can look at the shadows in a Monochrom image and see a subtle, but distinct advantage over shots from a similar color-capable digital camera. It’s not just a matter of blacker blacks, because you can process any digital image to skew towards darker hues. Where you’ll see a real difference is in the shadows, where the gradations appear smooth and detailed. There will be almost no digital distortion in the transitions from black to gray. And even though you’re viewing a monochrome version of a real-like scene, that black-and-white image will seem more life-life than a desaturated image from a color camera.

I realize that recreating the look from classic black-and-white movies isn’t on the bucket list of most photographers. However, if you’re into black-and-white photography—or simply want to see some fine examples of film composition and creative use of shadows—then you might check out the work of the great cinematographers.

For starters, you could take a look at Karl Freund (The Last Laugh and Metropolis), Carl Hoffmann (Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried, and Faust), Gregg Toland (The Grapes of Wrath, The Long Voyage Home, and Citizen Kane), Nicholas Musuraca (Stranger on the Third Floor), Robert Krasker (The Third Man), Russell Metty (Touch of Evil), and John Alton (T-Men, Raw Deal, He Walked by Night, and The Big Combo).

In his introduction to John Alton’s book Painting with Light, Todd McCarthy sums up what many of the cinematographers were trying to achieve with their shadowy monochrome images. “In the definitive noir period, roughly 1946-1951, no one’s blacks were blacker, shadows longer, contrasts stronger, or focus deeper than John Alton’s,” writes McCarthy. “Very often, the brightest object in the frame would be located at the furthest distance from the camera, in order to channel viewer concentration; often, the light would just manage to catch the rim of a hat, the edge of a gun, the smoke from a cigarette.”

Film noir sets were often illuminated with spot lighting or strategically placed backlights to create pools of light with extended shadows. Wide-angles lenses were favored for a deep focus. And those lenses were often stopped down to make the focus deeper and sharper. In some cases, the directors and cinematographers would use forced perspective to create the illusion of a greater depth of field than was possible given the limits of the lenses, film stock, lights, or available space.

We can’t duplicate the elaborate sets or megawatt lighting from the big studio films, but we can apply some of those same techniques. We can look for real-life environments that have extended shadows and backlit illumination. We can favor wide-angle lenses or stop down our standard lenses to achieve a deep focus. And we can process our images to approximate the tonal values associated with the great cinematographers.

These photos don’t show even a fraction of what the great cinematographers were able to capture on film. However, they’re far better than they might have been, had I not been able to see these classic films and unconsciously absorb their lessons about light, shadow, and form. All the photos were shot with a Leica M Monochrom camera. And I used a mix of Leica lenses: the 18mm Super-Elmar-M, 21mm Super-Elmar-M, 24mm Elmar-M, 24mm Summilux-M, 35mm Summilux-M, and 50mm Summilux-M.

In the photo titled Vegas Shadows #2, you can see the kind of long shadows that characterize the best work from cinematographers Gregg Toland and John Alton. Here the 35mm Summilux-M is able to capture an extraordinary amount of texture in the carpet. Notice how the shadows taper smoothly from a solid black in the middle of the frame to a dusty black at the bottom. Seeing these shadows at the end of the day, I sat down and waited for people to pass by. If you capture enough shots, you’ll find that at least one of them will be a standout image, such as this one. With these types of shadow shots, it’s not just a matter of waiting for the right light. You sometimes have to wait for other chance elements to fall into place.

Having a wide view from a 21mm lens doesn’t mean you have to fill up the entire frame. Empty space can be a powerful compositional element, especially if you want to focus the viewer’s attention elsewhere within the frame. With the photo titled Grand Central #9, the isolation of the lone figure is intensified by the black surrounding space. Without the detailed tonal shadows provided by the lens and camera, the emotional impact would be lost. Seeming to emerge from the light, the figure’s outstretched hand, mid-step stride, and introspective facial expression make for a compelling slice-of-life.

One of the great strengths of a wide-angle lens is being able to capture a broad view of a scene. And with that broad view, you’ll be able to place a person or object within a larger context. With the photo titled Fulton Center #1, the lone figure is lit from above. However, the light is diffused by the overcast weather and the reflective design of the architectural space. The downside to a wide-angle perspective is the increased opportunity for the brighter areas to burn out the details in the lowlight areas. This can be especially tricky with the Monochrom, where you don’t have the color channel info to help cover up your overexposure mistakes. As a result, I’ve found that it’s often best to underexpose a half stop or even a full stop when shooting with the Monochrom.

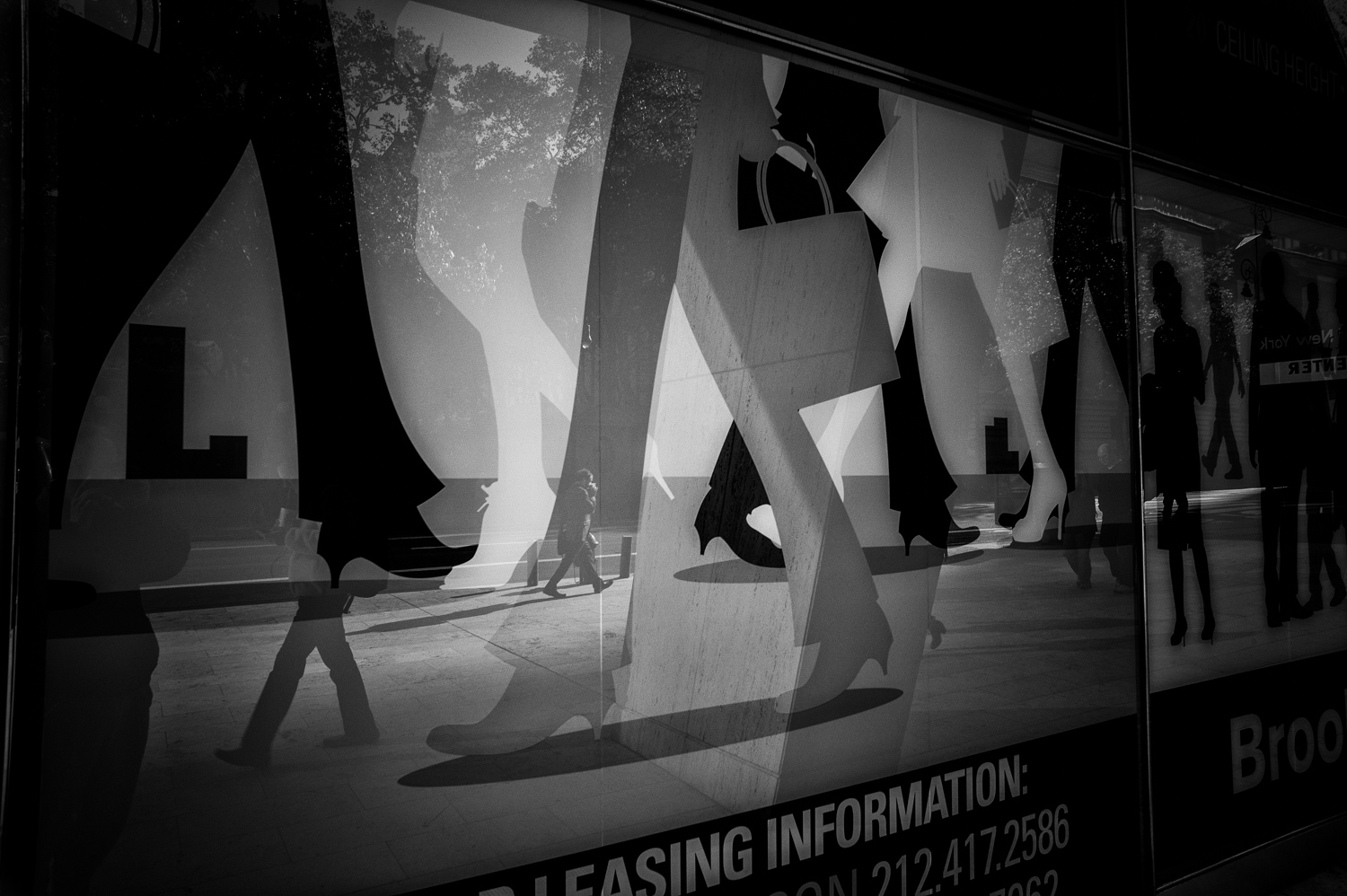

Sometimes you’ll find a setting where people, architecture, and human-created content are swirled together like melting Neapolitan ice cream. It’s a good opportunity to look for complex compositions where the different elements appear to interact with each other. This one is titled Cosmopolitan Lobby #14. Here the dark lighting and people in the lobby, when viewed alongside the LCD monitors, ceiling-mounted mirrors, and semi-reflective surfaces on the displays, all combine to provide a multifaceted shadow play. The segment program running on the displays seems to mirror the real people walking nearby. The end result is a pleasantly confusing canvas of gestures, postures, and outlines that are simultaneously real and unreal. This one was shot with the 21mm Super-Elmar-M, which provided a wide-enough view to take in the full range of elements.

If your black-and-white photography tends to explore long shadows and isolated light, then you may find that the Monochrom is uniquely qualified to capture your monochrome images in a full-frame format. Using it with Leica’s M-mount lenses, I’ve been able to replicate at least some of the aspects of the shadowy worlds associated with classic black-and-white cinematography.